Once in a while I find a good article to read when I browse through my favourite Chapter’s Indigo store. Last spring I picked up a copy of American Scientist, volume 104 (March-April 2016). I was totally intrigued by a story titled “Spring budburst in a changing climate“.

Budburst

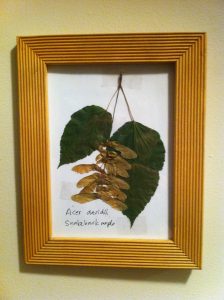

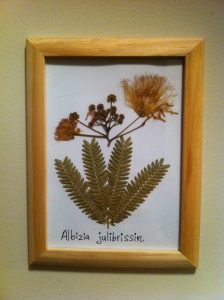

Budburst isn’t as extensively studied as flowering times. We know that trees respond to spring temperatures. As it warms up leaves emerge out of tree and shrub winter buds. What isn’t as well known is that man-made climate warming is affecting when leaves appear on trees and shrub and when they drop to the ground. Even less known is how budburst timing affects birds and insects, entire ecosystems and humans.

Leaf functions

Leaves play a critical role in photosynthesis. They absorb lots of carbon dioxide from the air and convert it to carbohydrates through photosynthesis, which are then transferred into wood and roots.

As new leaves emerge in spring and start photosynthesizing, global CO2 levels decline. Leaves also release water during this process which affects local climate and rainfall patterns.

Leaves also provide food for caterpillars, deer and other herbivores and they provide cover for birds and other wildlife.

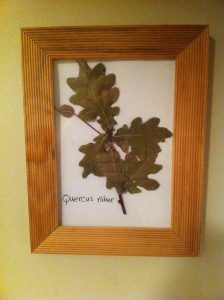

Thoreau’s Concord

It was in Concord in 1850s that Henry David Thoreau observed local plants and it was at Walden Pond that he wrote his classic Walden work. What I didn’t know was that Thoreau kept a record of leaf-out times for 43 woody plant species. So the study authors did their own research to compare the leaf-out times now to 1850s. And as expected, the mean date of leaf emergence has shifted from May 8 in Thoreau’s time to April 20 in recent years.

No big deal?

Eighteen days may not seem like a huge difference but it actually is. Consider the caterpillar which is used to eating young tender leaves. Now when he emerges, ready to eat he may be encountering older, tougher leaves. This could affect caterpillar populations and consequently, bird populations as birds arrive and look for caterpillars to eat.

Species differences

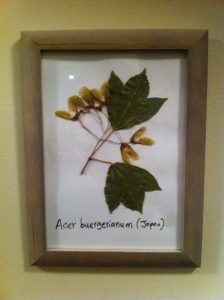

Since different species use different cues for budburst, a warming climate will affect each species differently. In some cases, warmer climate could help invasive species proliferate. One example is Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) which has minimal or no winter-chilling and day-length requirements for leafing out. It will push out new leaves after a week of warm weather. It forms thick stands that compete with native trees.

If native trees wait until late spring to leaf out, some invasive shrubs could increase their competitive advantage.

Late frosts

Another potential problem could be late frosts. As trees and shrubs push out their leaves earlier than usual they could be damaged by late frosts. Back to the Japanese barberry. This invasive species in North America combines early leafing out with a high degree of frost tolerance.

This article is worth studying in its entirety. The potential mismatches between tree and shrub leaf out and insect and bird feeding could create huge ecosystem problems. And it’s already happening.